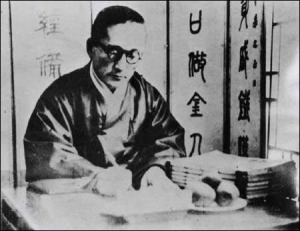

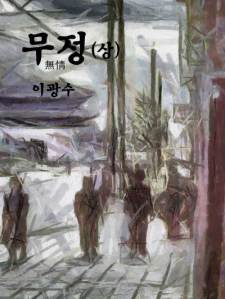

After dealing with the various discussions within South Korean scholarship on the emergence of Korea’s modern literature in earlier posts, and the almost unanimous agreement of Yi Kwangsu’s The Heartless as its very first product, I will now turn to a short historical overview of the literature that came afterwards.

In the period that Yi Kwangsu’s story came out, cultural and political life within Korean society had been severely restricted by the Japanese colonizer. Privately run newspapers were forced to closed down and the largest pre-colonial newspaper, the Korea Daily News (Taehan Maeil Shinbo 대한매일신보), became a state organ.

Strict rules on publication and censorship were established through the 1907 Newspaper Law and the 1909 Publication Law, made it very difficult to obtain a publishing permit.

Putting the lid on Korean intellectuals’ freedom of expression was an important cause for the 1919 March 1st Uprising. Even though the protests didn’t lead to a hoped for regaining of national sovereignty, it did lead to change in the cultural sphere.

The Cultural Policy was proclaimed in 1920, making it easier for Korean intellectuals to publish and voice their opinions. Immediately a publishing boom was visible, with 409 permits being given for the publication of magazines and journals in 1920 alone. This was in sharp contrast to the 40 permits that had been given out in the whole 10 previous years.

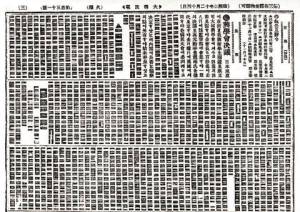

With their newfound freedom of expression, an air of optimism reigned among the intellectuals as if a new era had begun for Korean society. For the colonial power, censoring and monitoring the huge output of these Korean views, was a difficult task. In the beginning, newspapers who had printed an article deemed to be unsuitable for the censor were to be deleted by replacing it with dashes or broken lines. (making the newspaper articles look like “bricks”) Since this kept the deleted and censored parts visible to the reader and alerted them to illicit passages in the text, this kind of censorhsip was later replaced with no visible deletion (passages would just be left out).

The most serious issue for censors were related to 1) criticism of the emperor, 2) advocating class warfare, 3) revealing military information, or 4) criticism of the Government General.

Of course a cat-and-mouse game could be played with these censorship rules. Newspapers, for which it was too cumbersome to be screened before distribution, were permitted to start its print run before the issue went to the censor. In order to gain more readers, and establish itself as an anti-Japanese periodical, some newspapers would deliberately write articles that would surely be seized by the police. The trick then was to hire more delivery people and start printing earlier than usual, so that when the issue was banned, it would already be too late to seize them.

Poetry and serialized novels were almost exclusively to be found in the daily press and virtually all magazines and journals. With the repression of the previous years gone, a lively literature movement was established that soon split up into many different artistic and political groups.

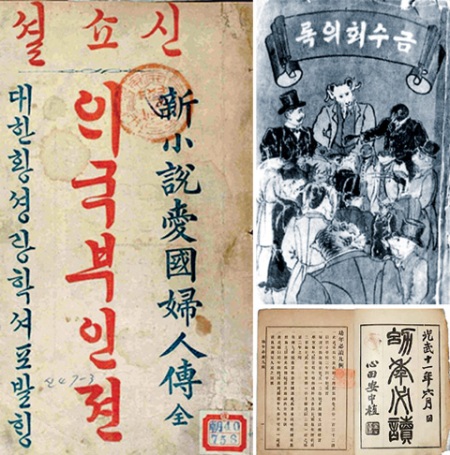

The earlier tendency to translate Western literary works was continued by Kim Ǒk through his magazine Artistic and Literary News from the West (T’aesŏ Munye Sinbo, 1918).

In Tokyo, Kim Dong-in and other writers were influenced by Japanese realism and established the magazine Creation (Ch’angcho, 1920).

Romantic poets like Hwang Sŏk-u and Pak Chonghwa would publish their poetry in Rose Village (Changmich’on, 1921).

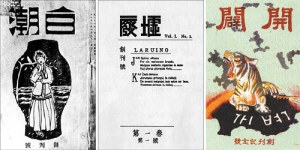

The magazines White Tide (Baekcho, 1920) and Ruins (P’yehŏ, 1920) were specifically set up for publishing “pure” literature, with the aim of making literature without a political or social reform ideological message, in reaction to the heavily didactic tone of earlier “enlightment” novels. Writers like Yŏm Sangsŏp and Kim Dong-in were experimenting with naturalist and romantic forms to establish such a view, of which Kim’s Potatoes (Kamcha, 1925) is one of the more famous stories in Korean literature.

Famous poems or poety collections from this period are Kim Sowŏl’s Azaleas (Chindallae-kkot, 1922) Yi Sanghwa’s Does Spring Come to Stolen Fields? (Ppeakkin ttŭr-edo bom-ŭi onŭnga?, 1926), Han Yong-un’s poetry collection The Silence of Love (Nim-ŭi Ch’immuk, 1926) and Sim Hun’s When that Day Comes (Kŭ nar-i omyŏn, never published during the colonial period due to censorship).

An important socialist literary group was established in 1925 with the KAPF (Korean Artists Proletarian Federation), whose aim it was to serve the cause of class liberation. They experimented with “socialist realism” to promote class consciousness among the intelligentsia and to expose the bad conditions of the minjung (proletarian masses). Cho Myŏnghŭi’s Nakdongkang River (Nakdongkan, 1927) and Yi Kiyŏng’s Fire Field (Hwajŏn) are prominent works in this regard. Since the advocation of class warfare was prohibited, this group had to deal with the constant harassment by the Japanese authorities, which many times led to strict surveillance, arrests, and heavy censorship.

Last but not least the magazine Genesis (Kaebyŏk, 1920) which was issued by the Ch’ŏndogyo religion, featured leftist literature, which sometimes featured stories by “New Tendency”(Shin Kyŏnghyang) leftists like Kim P’albong and Han Sŏrya, who deemed the poetry of romanticists like Yi Sanghwa and Hong Sayong to be too decadent.

Thus the 1920s can be seen as a very lively period in Korea’s literary history, although all these differing (political and literary) opinions and views would also be the genesis of the later (post-colonial) ideological differences that would appear on the peninsula.

Posted by jeromedewit

Posted by jeromedewit